On the cutting edge: A history of textile art

Textile art is something particularly special. Textiles stand out from other art forms, such as painting, photography or sculpture, because they manage to walk that line between practicality and beauty. It’s perhaps for this reason that textile art so often finds itself on the cutting edge of human interaction, despite sometimes facing a degree of snobbery from elsewhere in the art world. From the use of clothing to denote social status to the way in which fabric, folklore and storytelling are so intrinsically linked, textiles and creativity have always gone hand in hand.

The delicate nature of fabric means that early examples of textile art are rare. There are samples of clothing going back as far as ancient Egypt but it’s really during the medieval period that we start to see obviously decorative textiles. Both weaving and embroidery were techniques commonly used to create objects of great beauty - and great expense.

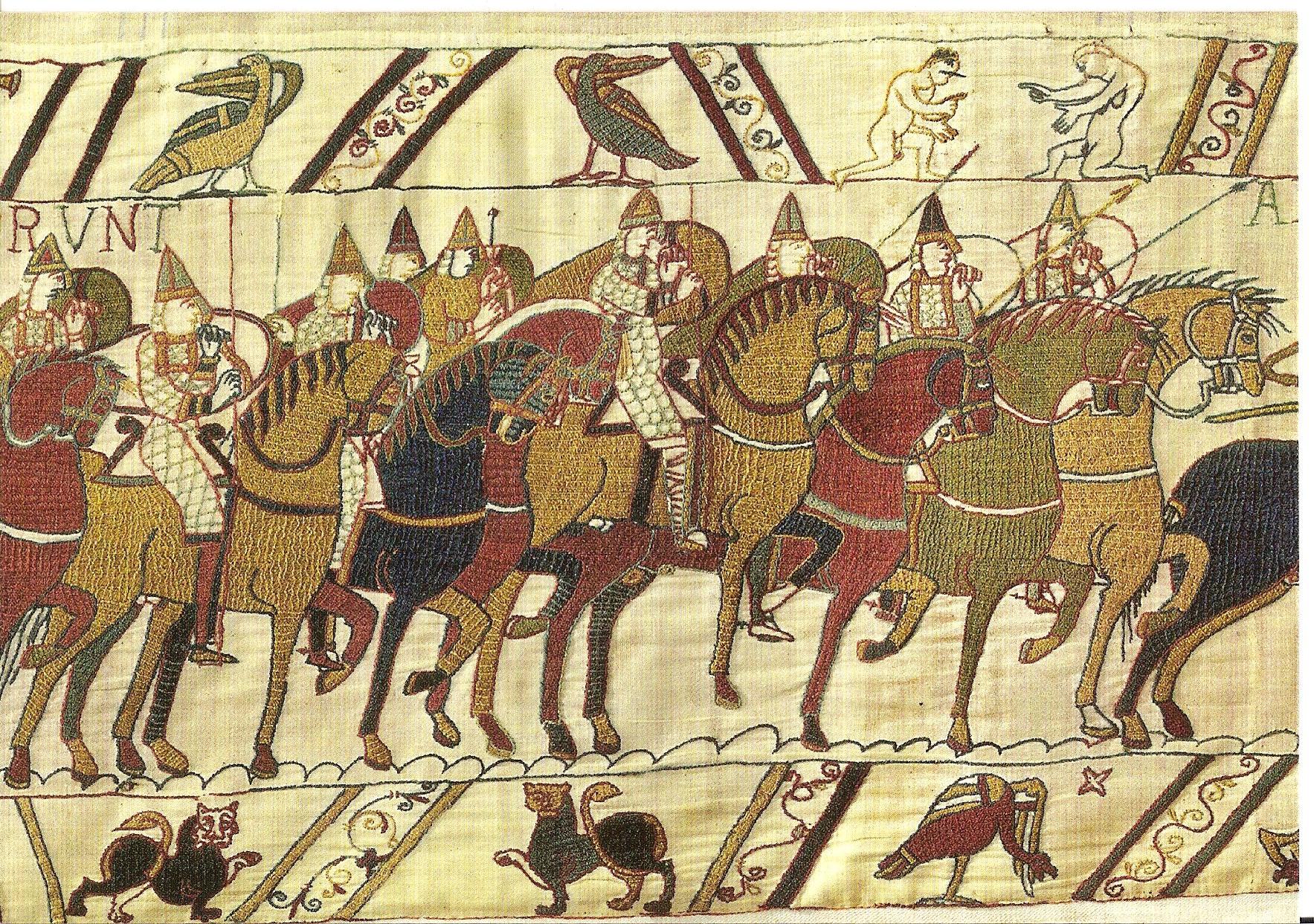

Probably the most famous example of early embroidery is one that’s known as something completely different. The Bayeux Tapestry isn’t actually a tapestry; it’s a piece of embroidered cloth. It’s also one of the earliest examples of textile art, dating from the 11th century and depicting the Norman Conquest of England. Here we see fabrics being used for something other than clothing or shelter; the craftswomen (for they were likely women) were employed to tell a story, a work of art to commemorate a momentous event in a way that everyone would be able to understand.

Bayeux tapestry

In the centuries that followed the Norman Conquest, however, it was English embroidery that dominated Europe. Opus anglicanum - or “English work” - was the art of delicate needlework that became hugely popular as a luxury product. The incredibly fine embroidery was used for both domestic and religious purposes but most of the surviving examples come from ecclesiastical contexts. High-ranking priests during the Middle Ages would be clothed in ceremonial attire, such as a cope (cloak) and chasuble (sleeveless tunic), covered with intricately embroidered religious iconography. Both the Steeple Aston and the Butler-Bowden copes, dating from the 14th century, show us the exceptional quality of this style of craftsmanship, where the lives of Christ and the saints were turned into wearable works of art. And opus anglicanum wasn’t found only on clothing; it was also used as a means of decorating other objects, such as the cover of the Felbrigge Psalter.

It was around this same time period that another very well-known form of textile art became popular across Europe: tapestry. Traditionally handwoven on a loom, tapestries performed a number of functions, from ceremonial to decorative to practical (insulating drafty buildings). Due to the degree of skill involved in their creation - and the fact that they were usually the result of a team effort between a designer, a painter and a weaver - tapestries were high status items, afforded only by the wealthy. Some of the finest examples were created in Arras, northern France, and were used as decoration by rich households all over Europe. It wasn’t uncommon for tapestries to be designed as sets, such as the magnificent Devonshire Hunting Tapestries from the 15th century. This collection of four separate tapestries illustrates hunting scenes with a variety of animals, a theme that would have been fun and familiar to medieval aristocrats.

Segment of one of the Devonshire Hunting tapestries

Scenes like those depicted in the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries provided visual entertainment for people at a time when literacy was low. However, tapestries could be used to tell a different kind of story - such as propaganda. The series of tapestries known as The Story of Abraham, commissioned by Henry VIII, not only functioned as a piece of high-status artwork; it’s believed that they were a tool to legitimise Henry’s position as head of the church at a time when his son - and therefore the future of his dynasty - had finally been born.

Tapestries were a particularly popular form of artwork because, unlike a painting, they were easily transported. This meant that they could be moved from one location to another with minimal risk of damage, something that was especially useful when it came to diplomacy. High profile individuals during the Middle Ages would use a baldachin or “cloth of state” woven with their personal ensignia to demonstrate their authority. The meeting-place of Henry VIII and Francis I of France in 1520 was famously known as “The Field of Cloth of Gold” partly due to the extravagant display of sumptuous textiles by both monarchs.

The Pazyryk Carpet

Across the globe, weaving was being used to create an alternative to the tapestries of medieval Europe. Carpets were just as portable, decorative and luxurious as tapestries but were instead used to cover floors, not walls. The earliest surviving carpet - the Pazyryk Carpet - amazingly dates from the 5th century BC, in what is now modern-day Armenia but what was then part of the Persian Empire. Historic evidence of carpets can be found all across Asia, but particularly in the Islamic world where the use of prayer rugs was - and continues to be - widespread. The Quran actually mentions carpets on several occasions, stating that they can be found among all the comforts of Paradise.

Pattern is significant in the design of Islamic carpets. Rather than relate a specific narrative as per the textile art of medieval Europe, it’s believed that the designs of Islamic fabrics (and other forms of decorative arts) have a philosophical meaning. The use of patterned motifs represents the importance of harmony and balance both in the world and the heavens. This symmetrical way of thinking and design can clearly be seen in the Ardabil carpet, created in 16th century Persia.

The Ardabil carpet

Despite being the poor relation of “high” art like painting, textile art has always managed to find itself at the forefront of technological and societal changes, such as the remarkable trade in purple dye throughout the Classical-era Mediterranean or the introduction of sumptuary laws to curb the consumption of extravagant goods during the Middle Ages. However, it was perhaps the Industrial Revolution during the 18th and 19th centuries that had the most dramatic impact on textiles. Up until that point, the production of all types of textiles - be that clothing, tapestries or just the raw materials - had been a laborious process. Everything was done by hand and, though this was time-consuming, it meant that individuals had greater control over what they produced - and what they charged. The invention of automated means of production, like the power loom, posed a threat to traditional livelihoods and sparked the Luddite rebellion as workers feared they would be replaced by machines.

While, on the one hand, the Luddites were probably justified in their concerns, the end of the 19th century actually saw a resurgence of traditional textile arts in the UK thanks to William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement. The Arts & Crafts movement was both a creative and a political powerhouse that advocated a return to old-fashioned methods of crafting, as well as economic and social reform. Exponents of the Arts & Crafts movement aimed to halt the perceived decline in standards brought about by the Industrial Revolution and they were heavily influenced by medieval or rustic styles of decoration.

William Morris, Forest Fabric - Charcoal

William Morris was a leading figure of the Arts & Crafts movement, and his impact is still felt in design today. Together with other luminaries such as Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Morris founded a decorative arts/interior design company that he eventually took sole control of: Morris & Co. Morris both designed and manufactured a range of furniture and decorative objects, but it’s perhaps his remarkable textiles that he is best known for. Unsatisfied with contemporary dyeing techniques, Morris chose to revert back to traditional, natural dyes such as indigo and cochineal, leading to more vibrant colours in his fabrics. His experiments with dyeing and silk weaving led him to open a factory in south-west London where he created over 600 designs for textiles. Morris also worked on carpets, such as the beautiful handwoven Bullerswood carpet, created at his home in Hammersmith. The upper and middle classes liked Morris’s designs not only because of their accessibility and their quality, but also because of his philosophy of total artistic control. He brought back the personal touch that the Industrial Revolution had removed.

Slowly but surely the decorative artists - including textile artists - came to be recognised as just as relevant as other fine artists and, in several cases, the mediums became less segregated. Sonia Delauny, co-founder of the Orphic art movement during the 20th century, was a painter, fashion designer and textile artist known for her use of bold colours and geometric shapes - even a quilt she made for her baby son is now in the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. Gunta Stötzl became the only female master at the Bauhaus school in Germany where she reinvigorated the textiles department. One of her aims was to move away from the idea of weaving as “women’s work” - and therefore separate from other art forms - so she utilised the same sort of language that was generally used when discussing modern paintings. Like Delauny, Stöltz used bold colours and patterns, as can be seen in her “Slit Tapestry Red/Green”.

Anni Albers weaving

Fellow German, Anni Albers, also studied at the Bauhaus where she discovered that only certain disciplines were available to her as a woman. She reluctantly took up weaving, under the tutelage of Gunta Stöltz, and eventually became head of the department. Albers also became the first textile artist to have a one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, elevating both her creative status and that of textile arts. The Tate Modern in London will be holding an exhibition of Albers’ work from 11th October 2018 to 27th January 2019.

Nike Davies-Okundaye, A Group of Friends

Today we have the likes of Nike Davies-Okundaye and Ann Hamilton representing contemporary textile art. Davies-Okundaye is a Nigerian textile designer focusing on traditional Nigerian textiles as a way of reviving a dying culture in her home country. She teaches free classes to young Nigerians and wants to use textile art to help disadvantaged women. Ann Hamilton is a multimedia artist who uses anything from photography, performance, textiles and other created objects to create large-scale installations. So it’s here, during the 21st century, that we finally see textile art given equal room and importance with other art forms. It’s about time.